Background

Sickle cell disease (SCD) is an inherited disorder of red blood cell (RBC) caused by a mutation in the beta-globin gene resulting in abnormal hemoglobin known as hemoglobin S (HbS) or the sickle hemoglobin. Several clinical variants of SCD have been elucidated, all driven by two fundamental pathophysiologic processes: RBC hemolysis and intermittent vaso-occlusive vasculopathy resulting in tissue ischemia/infarction. These two processes underscore the many complications and eventual multi-organ damage that may develop in patients with the most severe types of SCD.

Cardiopulmonary complications including heart failure, pulmonary hypertension and acute chest syndrome (ACS) are major drivers of morbidity and mortality among patients with SCD. With regards to ACS, patients often present with fever, cough and shortness of breath caused by vaso-occlusive crisis affecting the lungs. This is particular concerning in view of its similar features to symptomatic COVID-19 infection.

Methods

We retrospectively identified SCD patients with COVID-19 infection admitted to Beaumont hospitals in Michigan between March 1st 2020 and July 1st 2020. Data was abstracted using the ICD 10 code of U07. 1 for COVID-19, ICD 9 and 10 codes of 282.60 and D57 for sickle cell disease. We excluded patients with sickle cell trait. Data regarding the demographics, presentation, management and outcomes were abstracted.

Results

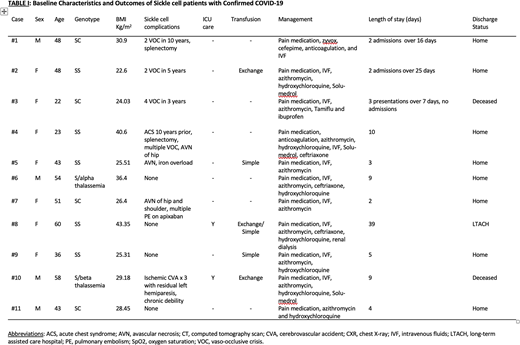

A total of eleven patients with sickle cell disease were identified as having a positive SARS-Cov19 polymerase chain reaction test (Table I). All were African American and predominantly female (64%) with a mean age of 44 (22-60) years and mean BMI of 30.2 kg/m2. Genotypes identified were HbSS in 5 (45%) patients, HbSC in 4 (36%), HbS/beta-thalassemia in 1 (9%) and HbS/alpha-thalassemia in 1 (9%). All of the patients had seen a haematologist since their diagnosis but none of the patients were on hydroxyurea, voxeloter, L-glutamine or crizanlizumab at admission. The predominant clinical presentation was fever, chest pain, chills, exertional shortness of breath and cough but this was not consistent across all patients. All the patients were managed with intravenous hydration, pain management as well as hydroxychloroquine/azithromycin per institutional guideline at that time. Three patients (cases 1-3) had recurrent visits to the hospital for similar symptoms and new bone pain crises. Case 1 had a pulmonary embolus which was evident on re-admission. Two patients (cases 3 and 10) succumbed to COVID-19. Two patients (cases 5 and 7) presented with bone pain crisis and no respiratory symptoms, but chest imaging was suggestive of COVID-19 infection necessitating treatment with antibiotics, possibly indicating that the virus can trigger vaso-occlusive crises without respiratory symptoms. Case 8 had a high Charlson comorbidity index and age over 60, had the lengthiest hospital stay complicated by renal failure and polyneuropathy, and was discharged to a long-term acute care facility: an outcome which is consistent with current data showing that the elderly and unfit patients are more likely to have a higher morbidity and mortality with COVID-19.

Conclusion

To date, there no compelling evidence to provide guidelines for the management of SCD patients with COVID-19. However, following existing recommendations in managing acute chest syndrome and those for COVID-19 symptomatic infection, is a good place to start. We continue to seek to improve management of these patients as new evidence of successful treatment emerges, and also encourage patients to participate in clinical trials.

No relevant conflicts of interest to declare.

Author notes

Asterisk with author names denotes non-ASH members.

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal